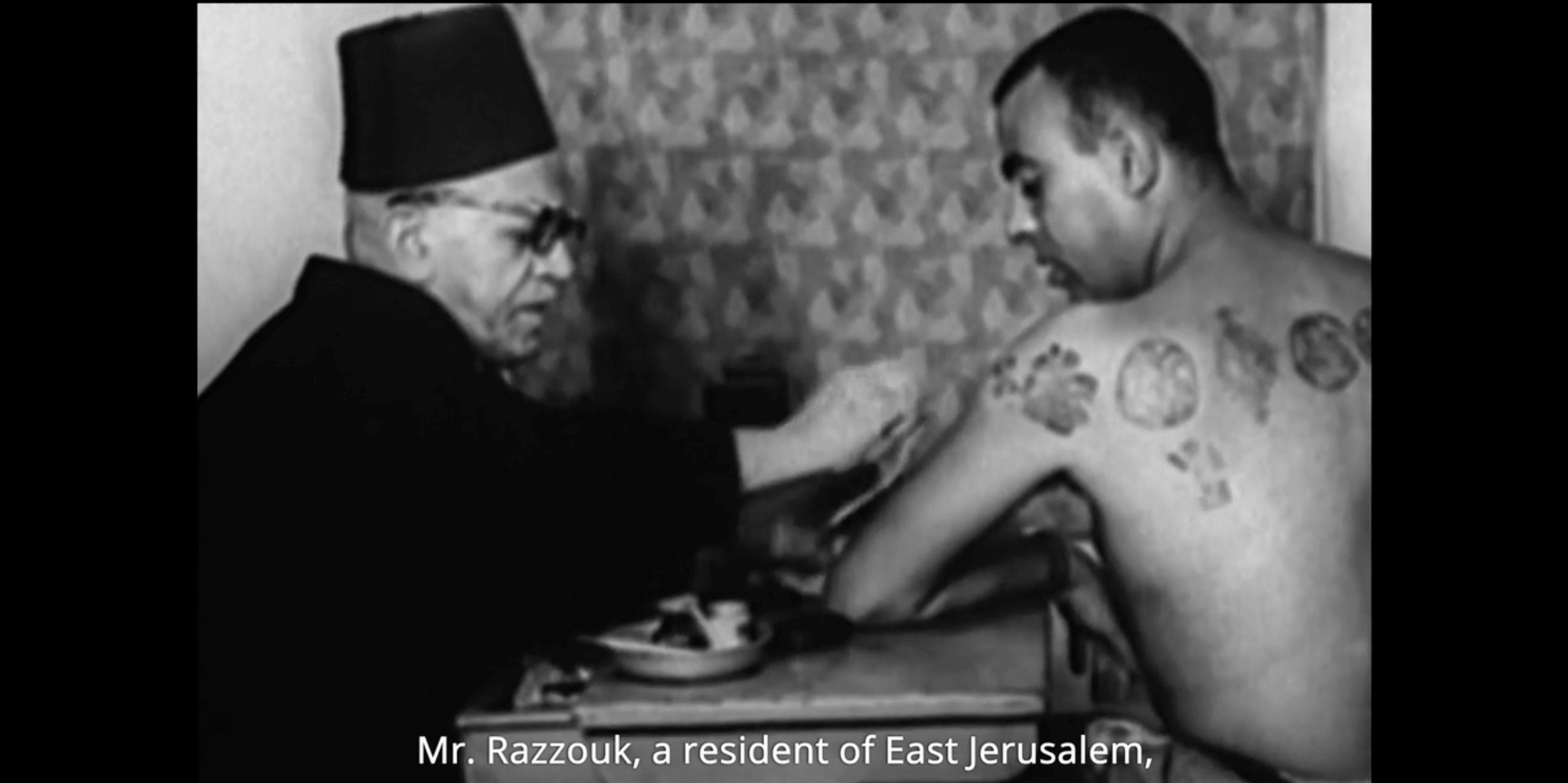

Yacub Razzouk Wassim’s grandfather, tattooing. Razzouk Tattoo

Yacub Razzouk Wassim’s grandfather, tattooing. Razzouk TattooBy Mira Fox

November 4, 2022

The Other Israel Film Festival seeks to “provide a window into the lives of Israelis and Palestinians from all walks of life and every corner of the land.”

In practice, this tends to favor documentaries about activist subjects. There’s films on the struggles of Palestinians living under occupation, historical investigations of atrocities committed by Israel during its formation, pieces on environmental crises in the Middle East and attempts to document the rare pockets of peaceful coexistence.

“Razzouk Tattoo” is a breath of fresh air this year, the only film on the docket that does not portray Palestinians in terms of their oppression. The documentary follows the Razzouks, a Coptic Christian family who immigrated to the Christian Quarter in Jerusalem’s Old City 500 years ago, bringing their trade with them: Christian tattooing.

The film focuses on the Razzouk family and their tradition of tattoos so much that it barely mentions Israel’s existence, much less the occupation. Only a brief mention of intifadas is made, as well as a short shot showing some machine gun-wielding soldiers in Old City streets near Razzouk’s tattoo shop.

But that’s not to say that it’s a lighthearted film. “Razzouk Tattoo” is neither an analysis of the roots of a niche practice nor a study of pilgrims in Jerusalem today. It’s a true-crime investigation.

Wassim Razzouk (current proprietor) of Razzouk’s tattoo shop still adheres to the tradition of tattooing. Using a wooden stamp, he imprints one of a collection of ancient designs — a Jerusalem Cross, the archangel Michael fighting a devil, the Annunciation — on his client’s arm, then traces over it with his needle and ink. As a nod towards modernity, he does make use of an automated tattoo machine.

According to the family, their ancestors brought with them stamps from Egypt. The stamps date back 500 years. But Wassim does not have all of them — and as the only family member still tattooing, he thinks he should. Here is the real drama.

Wassim inquires about his father’s stamps and finds that they had been part of familial conflict for several generations. But there’s more to the story — a cousin, Nelly, seems to have been murdered for her stamps.

At various points, multiple members of the family tried to go into the tattooing business, stealing stamps and tattooing equipment from each other and even sneaking the tattooing kit out of dead relative’s houses. However, only a small number of members of the family were able to master the art and became successful. Nelly was among them, as she was paranoid about the impending death.

The movie is a bit hard to follow at times — there are a lot of branches of the Razzouk family, and it’s hard to keep track of who is who and which now-deceased relative is which when people are referencing their husband or father or grandfather. Although the producers try to make things easier by zooming in on a family tree it just adds confusion.

The family members interviewed in the film don’t help to clarify the situation either. “Everyone loved her,” one Razzouk family member says of Nelly. “Nelly was full of hate,” says another. And the film goes off on tangents at times, detailing an abusive father’s relationship with his daughter, which seems to have little to do with the stamps.

In the end, despite the intrigue the film builds and its suspenseful music choices, there’s not much of a climax. Wassim doesn’t manage to reclaim the missing stamps or solve Nelly’s murder. The most interesting parts are the traditional documentary moments, where we learn nuggets about the history of tattooing or pilgrimage; the rest of it is just the internal drama of a family we’ve never met.

But it’s sort of delightful for that. “Razzouk Tattoo” feels both deeply tied to Jerusalem — after all, we’re talking about religious artifacts that are hundreds of years old — but also extremely pedestrian. It may be a more high stakes, exotic version of family drama, but at its heart, it’s still the sort of narrative that’s played out every day over inheritances and wills and ancestors.

It is an affirmation that Jerusalem’s life continues, even if there is political grandstanding or big moral narratives. The holy city is still populated by real people — regular, everyday people who hate each other for regular, everyday reasons.