The convention format is the same for most tattoo shows: large warehouse areas are converted to booths that allow subversive artists to use tattoo guns and other ink enthusiasts to trade or compete. The Godna Project, to be held at Delhi’s Khuli Khirkee studio on October 8 and 9, won’t be anything like that.

Instead, Chennai-based researcher and arts practitioner M Sahana Rao, 28, is bringing together indigenous tattoo artists from across India, in an effort to document and discuss India’s inking traditions. The irony is apparent right away: tattoos can be indelibly engraved. But, the knowledge of local hand-poke techniques, symbolism, needle-making, and the making indigenous inks are rapidly disappearing.

“So many communities have simply forgotten how they created and viewed tattooing,” Rao says. “I want to bring as many practitioners as I can to one place, so they can share knowledge with each other and with the rest of us.”

It’s more about remembering than reviving, she adds. S Janaki, a Kurumba tribal of weavers and shepherds in Ooty (Tamil Nadu), is 50 and one of the last tattoo artists in her community. She doesn’t recall much of the process of making some of the indigenous inks. Rao hopes to recollect the experience of meeting other people like her.

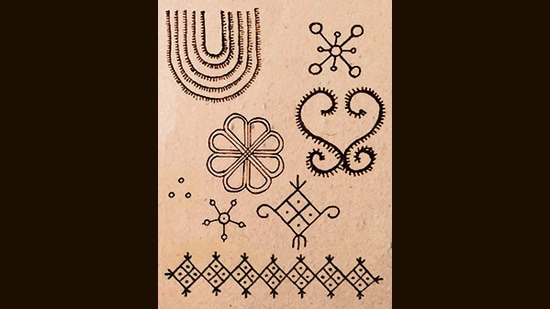

Moranngam Khaling (37), who has been studying the inking culture of the Naga people, as well as other tribes in Nagaland and Manipur, will discuss what local motifs these states have. Mangla Bai, 34 will show you how to use many needles simultaneously to create the thick designs created by the Baiga or Gond tribes in Madhya Pradesh.

The artists, along with practitioners Hanshi Bai, Lakhami and Kevala Nag from Chhattisgarh, will also be in conversation with Mushtak Khan, former deputy director of Delhi’s Crafts Museum. “India’s ministry of culture does not recognise tattoos as an art form,” says Rao. “But people in cities are getting interested in our indigenous motifs and techniques.”

Shomil Shah (a Mumbai-based tattoo artist) has been sharing traditional tattoo designs on Instagram. These styles include the dotted trajva marks worn by Rabari tribes in Gujarat and Rajasthan that once replaced jewellery. These motifs, together with other designs such as evil-eye patterns, kolams, and others, make up a rich virtual library for those who want to get traditional tattoos.

Mangla Bai claims that she enjoys tattooing young people during events in Mumbai. She also paints on canvas to keep the motifs fresh. It’s how designs have found a new life in the West as well. American tattoo artist Don Ed Hardy, who influenced popular tattoo styles in that country between the ’70s to the ’90s, licensed retailers to put his designs on clothes and accessories under the Ed Hardy label in the 2000s, giving them a wider audience. Katherine von Drachenberg’s tattoo art and methods were featured on the reality TV series LA Ink. She has since created a line of beauty products that are decorated with her designs.

The Godna Project offers workshops and tattoo sessions with Arjel, a Delhi-based Nepali artists. He was trained in Baiga tattooing by Mangla Bai. He then hand-pokes his design using native tools and needles.

“Tattoos have been in use around the world for centuries,” says Rao. The body of a man whom scientists call Ötzi or the Iceman, likely buried in an avalanche along what is now the Austrian-Italian border around 3250 BCE, had 61 tattoos across his body, including on his left wrist, lower legs, lower back and torso. “Humans have used tattoos as social markers, rites of passage, decoration, and as indelible marks we can carry into the afterlife. Among the Banjaras of Karnataka, tattoos are also therapy – aching joints are covered in splotches of ink in the belief that they relieve pain. Much of this is disappearing even before we can study it.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rachel Lopez is a writer and editor at the Hindustan Times. She has experience with Vogue, Time Out, and the Times Group and is interested in city history, culture and internet.