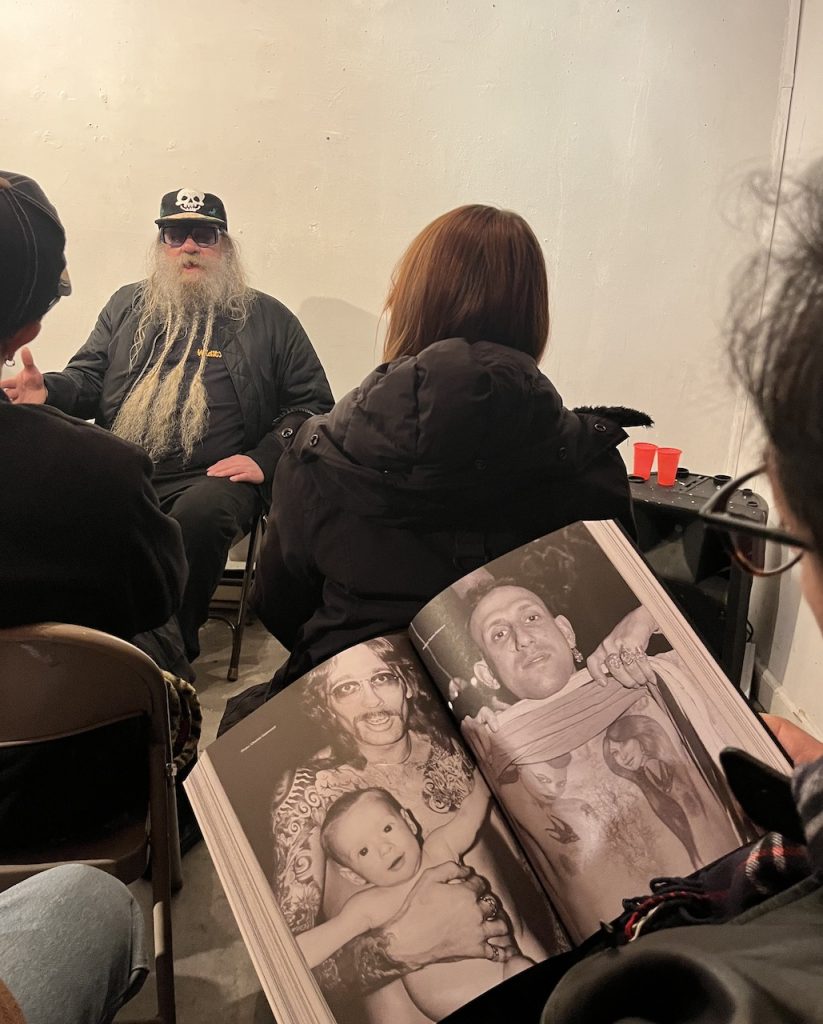

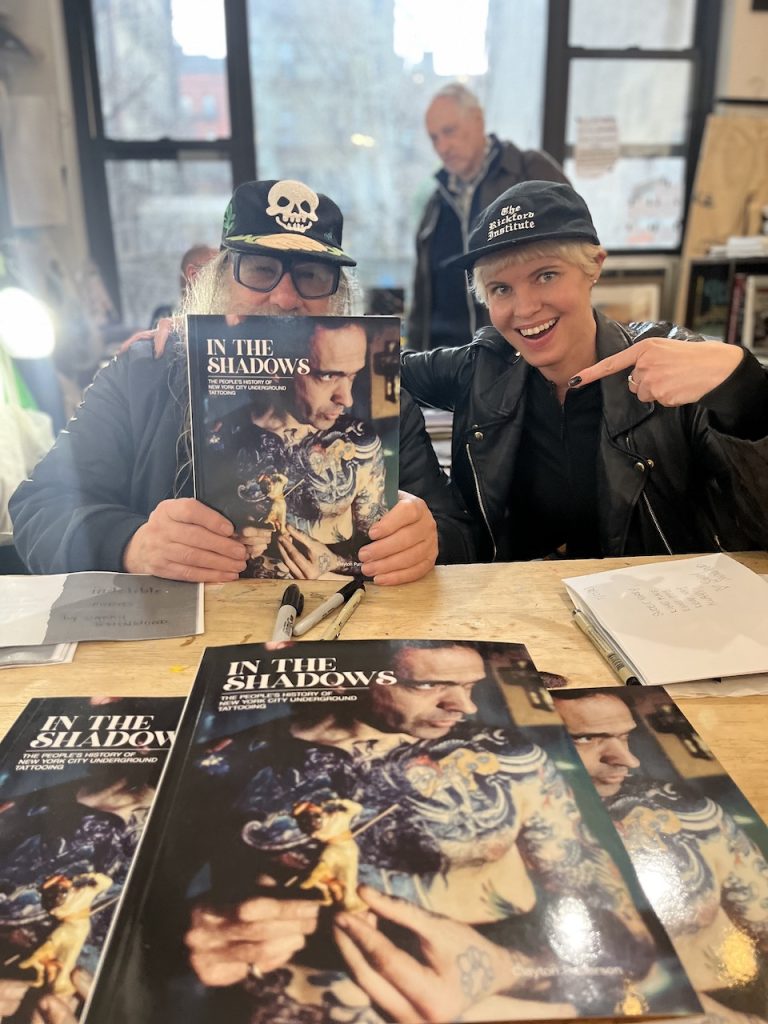

Clayton Patterson is doing a book signing for “In the Shadows” earlier this year on the Lower East Side. He flashed an “L” sign for L.E.S. (Photo by Destiny Mata).

They left their mark: New book tells the story of N.Y.C.’s underground tattoo years.

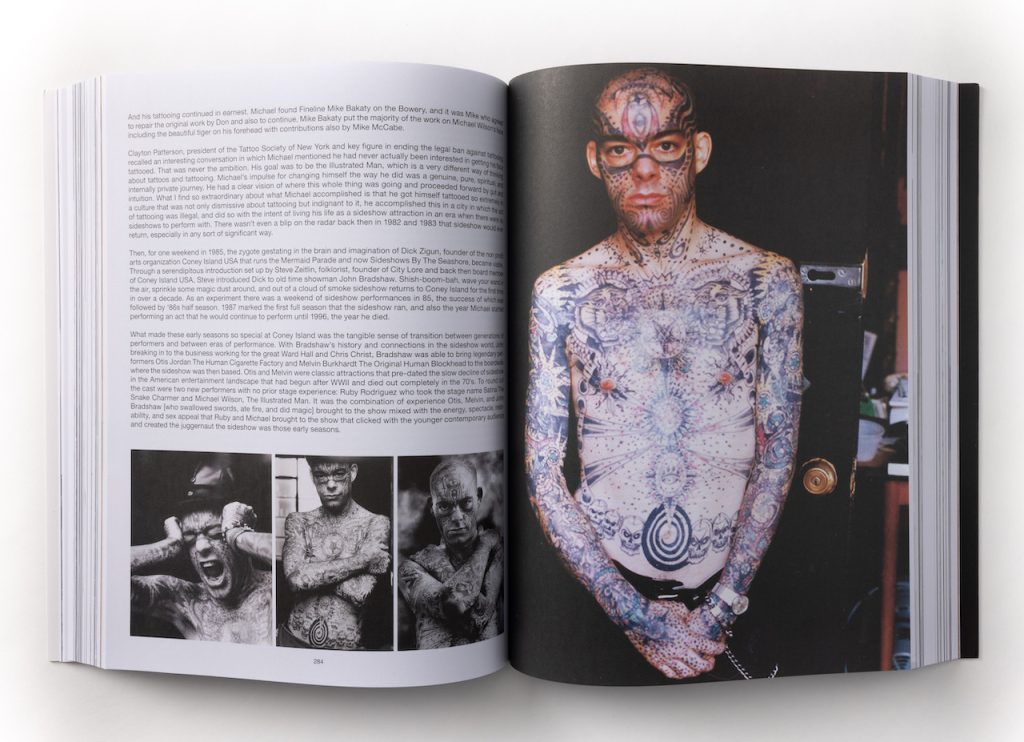

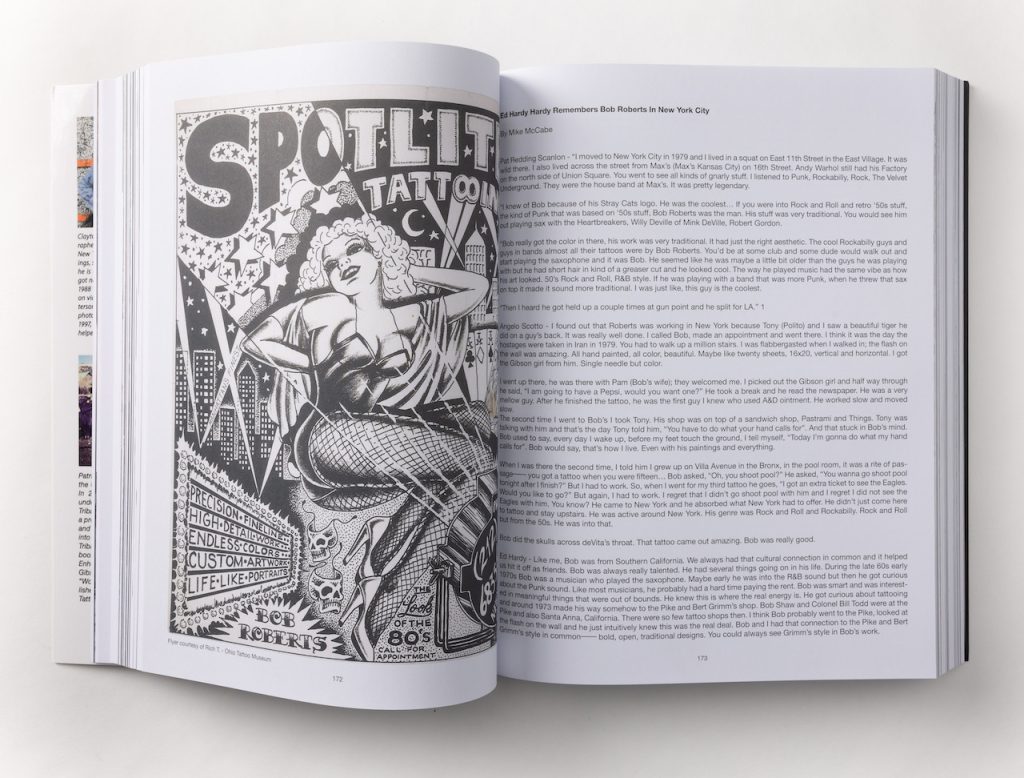

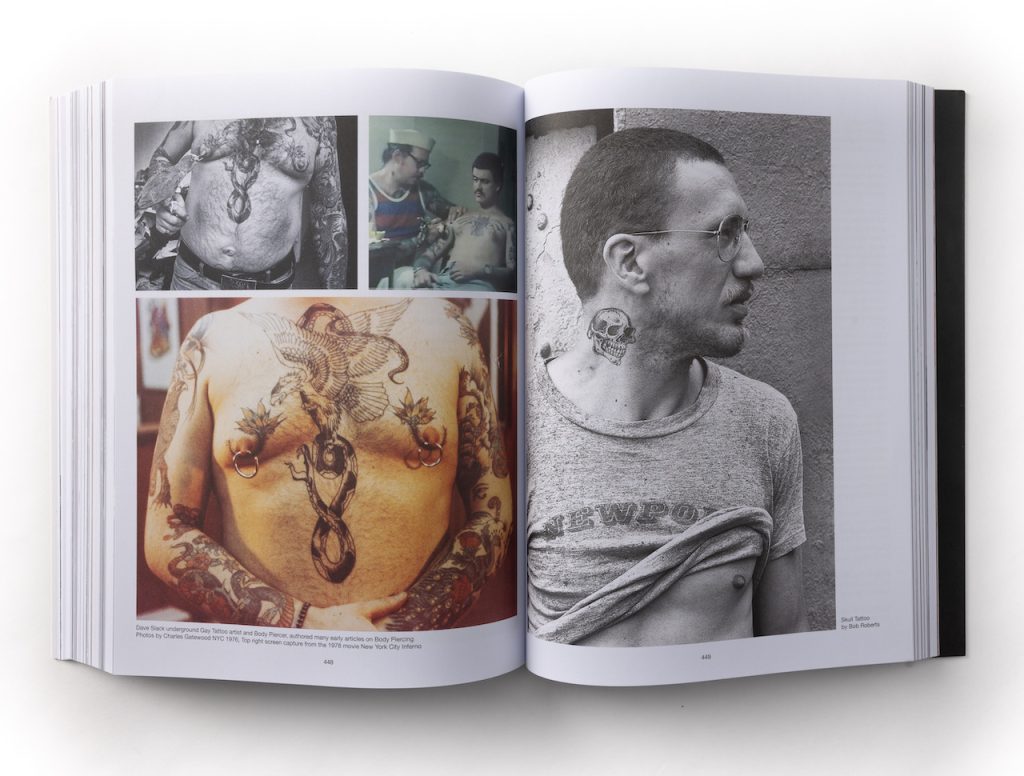

Weighing in at 5 pounds and running 600 pages, Clayton Patterson’s “In the Shadows: The People’s History of New York City Underground Tattooing” is the definitive book on the decorative art form’s evolution from the margins to the mainstream.

Nearly a decade in the making, the lavishly illustrated tome was released earlier this year by Tribal Publishing, an outfit headed by tattoo aficionado Patrick Kitzel. Paterson is listed as the book’s editor-in-chief and Kitzel as its content arranger and designer.

The prolific Patterson — who chides himself that the tome “took too long to finish” — has completed Volume II and is already at work on Volume III.

“In the Shadows” includes the earlier history of skin art, but its heart is from 1961 to 1997 — when tattooing was illegal in New York City. The ban was instituted after an alleged Hepatitis B outbreak in the early ’60s — though another theory says it was part of an effort to “clean up” the city before the 1964 New York World’s Fair.

The Village Sun recently sat down with the Lower East Side documentarian in his Essex Street storefront behind its accordion window gate — the building was formerly a dress shop — to talk about tattoo culture Downtown and beyond.

“This book has taken me nine years to do,” Patterson said. “Most of my books are anthologies. I do anthologies because I don’t want it to be my point of view; I want it to be fair. I want it to be unbiased. I tend to have a radical point of view.”

Among his other ambitious anthologies are “Resistance: A Radical Social and Political History of the Lower East Side” (2006) and “Jews: A People’s History of the Lower East Side: Volumes I, II, and III.” (2012). Patterson is also known for recording the most extensive video of the Tompkins Square Riot of 1988, back before everyone had cell phone cameras.

Befitting Patterson’s insatiable urge to document, the hefty book sports chapters on a wide array of topics, from profiles of tattoo artists, Lower East Side gang tattoo culture, biker tattoo photographers, and tattoo magazines to queer tattooing, hardcore punk rock tattoos, and even the Long Island tattoo scene.

As for why tattooing was outlawed before, it was partly just prejudice, in his view.

“Tattooing was blue collar — cops, construction workers,” he said. “Tattooing was considered very low brow. People were against low-brow culture.”

Patterson’s involvement with the underground tattoo scene started around 1986 when he spotted an ad in The Village Voice for a club whose members were interested in body art — from tattoos and body piercing to plastic surgery. The meetings of the club — the Tattoo and Body Art Society — were held at East Village artist and writer Uri Kapralov’s 6th Sense Gallery.

After Roger Kaufman could no longer keep the group going, it was taken over by filmmaker Ari Rousimoff and Patterson. They refocused it solely on tattooing, renaming it the Tattoo Society of New York, and held regular meetings on the first Monday night of each month.

“We used to have 100 people,” Patterson recalled. “We would have entertainment, fashion shows, tattoo contests. It was $5 to get in.”

Rousimoff eventually headed off more into art and film, so Patterson became president of the T.S.N.Y. For 15 years, he and his wife, Elsa Rensaa, put on the International Tattoo Convention at Roseland Ballroom. At one point, Rensaa was even personally inking hardened Lower East Side gang members. Patterson published several issues in a magazine called the Tattoo Gazette.

But after 1997, when New York legalized tattooing, the club disbanded.

Patterson said he was part of a core group that helped push for legalization, including then-Councilmember Kathryn Freed and Wes Wood, who ran a tattoo shop and supply business.

In the meantime, Patterson, in 1995, had also gotten involved with Wild Style, a European tattoo and sideshow festival, and would cross the pond annually to participate in the event. However, Europe, in terms of tattoo arts, “was about five years behind America,” he noted.

Not surprisingly, Patterson sports some skin art himself, though not an extreme amount. All of his tattoos are hidden under his clothes.

He got — or instead gave himself — his first that when he was just a kid growing up in the foothills in Calgary, Alberta.

“I tattooed myself when I was 12 years old — a little ‘C.P.’ right here,” he said, rolling up his left sleeve above the wrist to reveal the initials, plus a small cross with rays beaming from it. “I tattooed some other people.”

Called a “skin poke,” he would do it with three needles and a matchstick bound together with a rubber band, using India ink, usually in a basement or garage.

As it turned out, tattooing was just one early expression of a theme in Patterson’s life.

“I’ve been interested in Outsider Art,” he explained. “I’ve always enjoyed things that were underground.”

In the 1980s, with MTV music videos featuring heavily tattooed rock stars, skin art began increasingly mainstream, continuing a renaissance in the 1970s.

“What you started getting was [tattoo artist] Lyle Tuttle doing like a small wristband of flowers or leaves,” Patterson said. “Then you started getting into Ozzy Osbourne had a tattoo…and punk and hardcore [punk]. There were a lot of tattoos…California, [tattoo artist] Ed Hardy…Guns N’ Roses, Rolling Stones, the Stray Cats. Music is a large dictator of style culture.”

Add in social media’s influence, and today an estimated 30 percent of Americans have tats — while around 40 percent or more of people under age 29 have at least one — with the number of inked women said to outnumber inked men slightly.

Asked what he thinks of nonpermanent tattoos designed to fade over time, he was skeptical but added, “I won’t judge it.”

On the subject of facial tattoos, though, Patterson said it should be carefully considered beforehand — even though there is laser removal.

“My advice to kids is [if you want] to make a mark that’s permanent in a visible place — you have to give that thought,” he said. “Tattoo artists traditionally would not do hands or necks or faces: There always could be cases where the person changes their mind, and they didn’t want to be responsible for that. … Vali Myers tattooed her face,” he noted, referring to the late bohemian artist and dancer.

Similarly, he said he once advised a chef he knew not to tattoo his hands, telling him, “You could be limiting yourself.”

Another group that might want to think twice about getting tattoos is politicians, Patterson noted. Then again, there’s Brooklyn Councilmember Justin Brannon, who played bass in hardcore punk bands before entering politics — and has his shirtsleeves rolled up in his official photo to show off his forearm tattoos.

Tattoos have spread into every level of society. Despite skin ink’s strong roots in working-class, military, and prison culture, it also became trendy with the upper class in Victorian England.

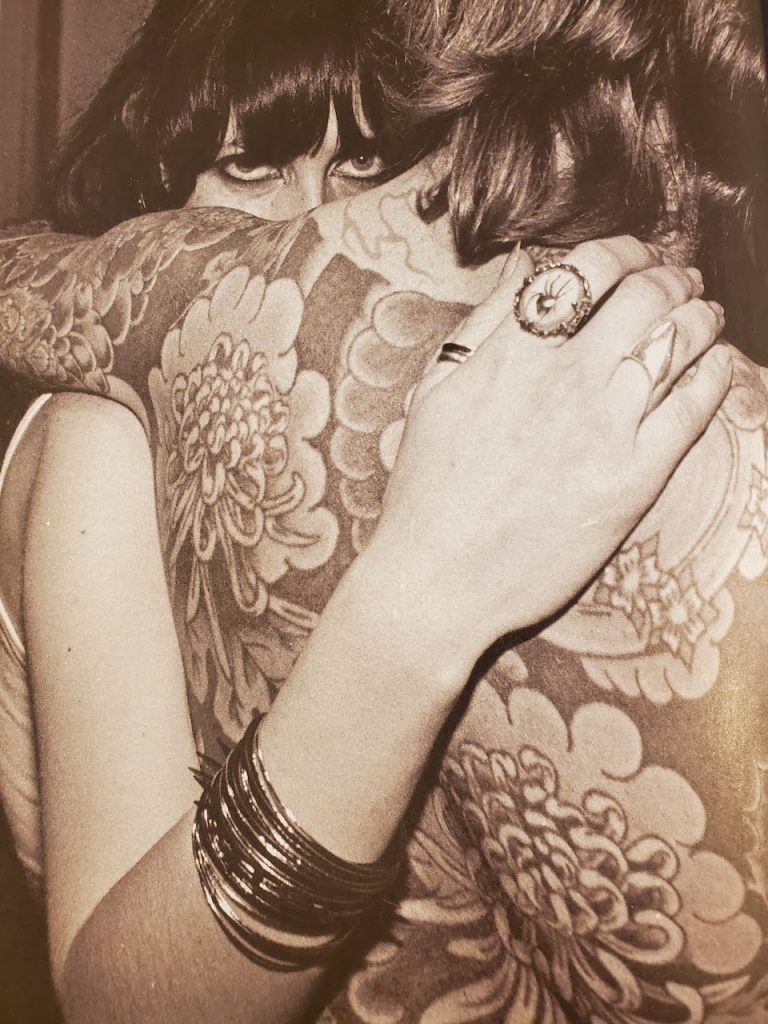

“Churchill’s mother had a tattoo,” Patterson noted. “She had a wristband, like Janis Joplin. Rich people used to go to Japan in the early 20th century to get tattoos — that’s a long boat ride.”

But it’s been a long time since those extravagant tattoo boat journeys and a while since the Big Apple finally legalized the art. Today, tattooing is practically as standard — and as easy — as getting a manicure.

“It’s beyond the mainstream,” Patterson shrugged. “There are high-end tattoo shops where you can spend $1,500 an hour to get tattooed.”

Asked if the “fad” of tattoos will wane, as all fads eventually do, Patterson said, “No. There’s an instinct in people to be marked…. It feels like you have control over your body, in a way. …

“There are lots of reasons to get tattoos. For some people, it’s a real calling — exotic, rebel. [Just] criminal, military, working-class — not anymore. Everybody has tattoos — except for people who follow strict religious doctrine.”

There is a Jewish prohibition against tattooing. Leviticus 19:28 states, “You shall not make gashes in your flesh for the dead nor incise any marks on yourself: I am the Lord.”

However, Patterson noted “Lew the Jew” was the moniker of a famous historic New York City ink artist. He’s in the book.

“I guarantee you have tattooed rabbis — guarantee it,” he added.

Patterson will do a book signing for “In the Shadows: The People’s History of New York City Underground Tattooing” at Village Works bookstore, at 12 St. Mark’s Place, on Sun., Aug. 27, from 4 p.m. to 8 p.m. You can also order the book ($70) on myshopify.com or amazon.com.

Comment and share on this article: